Talked with Ed about dreaming of Arnie. We were sitting in the back window and middle seats of a moving car. He was questioning me, looking me directly in the eyes, listening to me attentively, as I explained to him my project. That I had a desire to combine the work I was doing at the assembly with stuff from my past. Then he said to me, “Wes, how will you do that?” precisely anticipating the gap I was ready to fill. “With this thing I’m calling the underimage.” I didn’t even need to explain the concept, or how I saw it working. He just knew.

Ed called me on WhatsApp and immediately began to psychoanalyze the dream. He interpreted Arnie as the embodiment of a general desire I have to be witnessed, to feel seen, for my understanding and use of that concept, the underimage. I didn’t disagree, but said I also wanted to hold space for this actually being something that changes my relationship to, and thus my experience of, Arnie. I found Arnie (dream Arnie’s) witnessing of my thought healing, and I accept him more for it.

outside the airplane’s fuselage i feel no cold, only the exhilarating loneliness of having a secret. everything is white, i can flip on and off the deflecting stream of water particles coming from the sideways-turned nose of the plane. before, my parents visit. i’m in barcelona. my apartment is temporary, big but little light. i come home one night with them to find they’ve had it totally refurbished. green slate countertops, a new puppy, a cut-out window with still no direct light, i asked them. i know i’ve left planes before in my mind. with my mind i have this power. i can fly through the air, zooming closer, staying far away, seeing the plane far off like a beached whale on a cloud. i know i can’t reenter. as long as i hold onto the fuselage as we descend, i should be fine. until then, i’m free. i can hear a soft hum as if i were in the cabin. otherwise, it’s as soundless as a snowfield. i have a girlfriend and the puppy. i take my parents to do things they don’t do in the exact way i want them too. it’s like they don’t get that i want them to see how i like to do things. we see a movie maybe about a dancer. my apartment is in a shopping center. earlier or later i eat a messy chocolate bar and try to sneak into a glamorous apartment complex. the doorman turns me away, obviously. a tall and beautiful woman who’s going inside laughs at me and says, of course they knew you didn’t live here because you’re eating that brand of chocolate bar. i notice then its sticky black upon my lips. i walk home, and that’s when i discover the refurbishments to my apartment. they did it without asking me. i’m angry and lonely. they see not me but the part of me i use to keep them from seeing me. the water particle stream bows a wide arc off the sideways-turned nose of the plane. i wedge my fingers between metal fuselage pieces. we descend. i’m ok with dying if that’s just what happens. sometimes a secret carries this burden. we land with a slight bump where i intuitively sense is Heathrow. i casually crawl off the hull and walk toward the front door of the plane—it’s like a bus. the door is open, the driver on break. the security guard at the back has already packed my bag for me. i’m surprised they don’t know or don’t care i was flying outside the cabin. i wonder if i can always do that now, to pass the time while flying, if it’s worth it to bear this secret and its fear of dying. i enter Heathrow. it’s like a mall: huge plasma TV’s, chaotic consumer movement that feels as lonely as the sky.

In the atmosphere between my field site in Barcelona and my home in Minneapolis…

“Yea, oh, you know something cool? Well, I donno if cool is the right word. But, yea,” he says as his breath quickens in excitement, “about a week ago I woke up and was having a panic attack. I never got them before, but that morning I did.”

“Woah,” I said, not really knowing what to say but wanting to keep him talking.

“Yea, and so, for like a week I had this low level anxiety. It felt like I was always on the verge of having another one. When I worked in the yard, I’d get out of breath really quickly and get hot and sweaty and I’d have to come in and take a cold shower just to cool down, but then later I’d sometimes get real cold and shut all the AC’s off and just lie down in a pile of wool blankets on the sofa, shivering.”

“Woah,” I said again, uncouthly, I felt.

“Yea, so I was like, gosh, this is weird, and I’m wondering if I should go see a therapist or something. Then, after about a week—yea, musta been a week and a half—one morning I was reading the paper, drinking my morning cup of coffee, and I suddenly remembered that I had actually had a panic attack as a child. I musta been like ten. We were at the farm, playing, building forts with the haybales in the hayloft. You remember the hayloft, right? You and I usta play basketball in there and swing allll the way across it on those loooong ropes that were for hoisting—is hoisting the right word?—yea, hoisting up the bales of hay. So, gosh, it musta been B R and I were making hay forts—you remember doing that, right?—those tight tunnels that you could just barely crawl through [he makes an arm over arm motion as if he were swimming]. And all of a sudden the haybales collapsed on top of me. I don’t know if B R knocked them over or what, you know, we were boys always antagonizing each other, and I started to have this panic attack. All that poky hay in my skin and being unable to move. That’s the only time I’d ever had a panic attack, and I had forgot about it till that morning while I was reading the paper, drinking my coffee. And you know what’s cool?, when I remembered that memory that I had as a kid, I also remembered that the morning of the most recent panic attack, I had actually woken up from a dream I was having where I was dreaming about those hay bales falling on me again.

Then, when I remembered the dream and that original memory playing as a kid, the panic attacks stopped.”

We step outside into the backyard, and he grabs two lawn chairs and sets them up, one at a time, in a way that feels too intimate for me. They are about four feet from each other’s open mesh mouths. He and I sit, and we begin to talk.

I am stopping off at home on my way to the field, as I usually do before any major life shift. I look around me. There were years I never thought I’d leave this yard, the surrounding neighborhood.

“You always liked to have a conversation,” he says to me, emphasizing the speech utterance’s ending in the way only a parent speaking with the immutable force of parenthood can. I resented him for the performance of his authority over me.

The humidity in Minneapolis is so thick I can’t help but bring it into these words, too. I’m pitting out of one of the black shirts that I’ve begun to wear like a uniform. He continues, I never knew how to be a father to you because I never had a father neither. I always imagined that I’d come into another kid’s life like I always wanted a father to come into mine. By hopping over the fence. Just showing up one day.

I look at the chain-link fence beyond his shoulder; then on down the row of yards to the Little House, when it was still his and then when it was ours. It’s now some new family’s. When we moved onto the block, he lived just four houses down. My brother and I found him and introduced him to Mom as the cool guy down the street who fixed our bikes and gave us oven-hot cookies.

I dream that one day I will find someone who loves me for how I want to be loved. For how I want to feel seen. I want to feel important. I want to be accepted for who I am. I want the firm stillness of a beautiful woman who loves me for who I am. Not because I am a man. Am I even a man? Sometimes I think I’m a lesbian. Sometimes I want a man strong and distant enough to gather all my leaving into what I don’t yet know: Hey, what do you want to do today? I just want to do boy things. In your arms, in your living room.

Dad swells against his skin, which is green from the formaldehyde. His thinning hair lies artificially neat across his forehead as if it were seaweed the ocean keeps pulling into straight lines as it withdraws from the sand. A huddle of questions and confusions dressed in as-close-to-black-as-we-dared-to-bring assume a circle around him.

“Dad is in the Veteran Affairs Hospital in Seattle,” I hear Mom say on the other end of my Motorola Razor. I am on break from class at community college. “Do you want to go see him?”

We drive to save money and miss his death by a night. The other brothers get to hear his last words. The lights of the semis on I-80 guide us through Washington’s fog as if they were landing strips. They had last say over his soul. I wouldn’t have tried, as they did, successfully I heard, to “save” his soul; I wanted to know if he loved me. I wanted to know if he ever thought about me.

What part of who I am is from him?

I, too, wound up with only the bottle to kiss my lips. I could not speak my pain. How did I end up like him: drinking myself to sleep in a land that was not my home? Far from my family. I hadn’t learned that to heal I would have to speak about all the things no one else does. That I would have to take on both the status of monster and saint. That I would, even now, struggle to feel somewhere between causing us harm and healing us.

When big bro enters the giant community house for the families of active duty military personnel who are in the VA hospital, Dad’s widow bursts into tears because he looks just like Dad did. Their five year old son runs around, like comic relief making us all grin big, impossible smiles.

I follow and then lose track of new-grandpa’s pickup in Seattle’s verdant sprawl. Somehow someone’s managed to choose a funeral home in the quickening stasis that follows his time of death. I step into the funeral hall wearing a grey hoodie and notice the hall’s giant wood-beam rafters. There is a Black minister and a Black piano player. We are not all white: Dad’s third wife and widow are Korean and Japanese respectively. Dad left Mom while we were living in Japan together to be with the Korean woman, whose name I can’t remember now. Together, they had two sons, and later, Dad had one more, with M, the Japanese woman.

I watch all the Moms huddle together in a pew. Their collective weeping puzzles me. I feel left out, on my own. I look down at my dry palms and wonder if I’m dead inside because I can’t seem to cry. New-grandma turns to me and whispers it’s a shame about the negros. nodding toward the minister and piano player. But I kind of like this impromptu gathering. It fits our hodge-podge family, I wanted to plead, it’s beautiful in its own way! Your father deserved better. I felt embarrassed to know her, to have my name tied to hers. I didn’t know what to say.

About a year later, I go and stay with Dad’s side of the family for the first time. They are mostly farmers who live in Western Oregon. Although the winter air is above freezing, I feel it enter my bones like water through a strainer.

I went to visit them because I wanted to know who they were. What of them might be in me, too. Not only that, I went because at Dad’s funeral, Grandpa had told me that he has, in a shoebox, all the letters Dad had ever written to him. Dad had entered the Marines at the age of eighteen. Although no one will tell me the full story, what I’ve pieced together is that around his eighteen birthday, Dad got in some kind of trouble with the law. They then gave him a choice: time in jail or military service. The first letter’s return address is from the Marine base in San Diego. Together, the letters say very little of what interested me. They talk a lot about the weather, what Dad was working on. I can’t really remember many more specific details: A new house in North Carolina. A post-card of the bullfighting arena in Valencia. A late-night, surprise helicopter mission. What I do remember most is the absence of mentions of my brother and I. It was as if even in the letters he anticipated that I’d come searching for answers, and that even there he couldn’t face me.

We came all this way found ourselves poor on a foreign shore just the same.

In the masculine economy where a bomb can

bring back

time

only by obliterating any future

I want Dad to be the baddest motherfucker of them all.

Humid cologne escaping the neckline of his Hawaiian

shirt, like fog rolling forth

from his prairie skin. Hey, guys. Did you have

a hard time finding me?

I came here yesterday. he said.

With the time change, I messed

up your arrival date.

I stand accumulating the rain his August-

heavy hug as if it were the only thing to do.

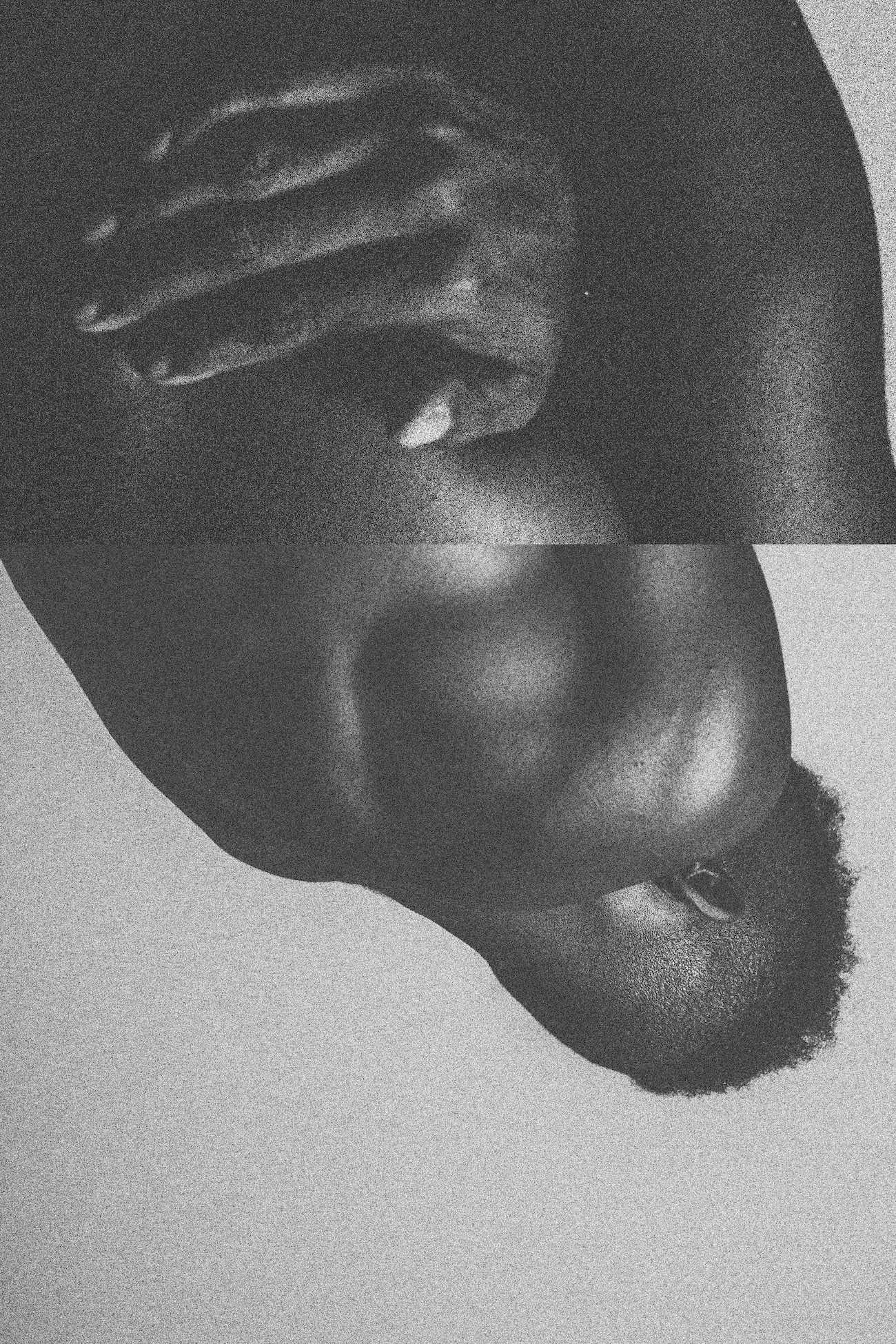

Original photo by Sam Burriss.