My keyboard is killing me.

Too dramatic? I write the sentence out and delete it, write it and delete. What if my keyboard is killing me? Can I face it if it’s true? Does it matter if I do?

There’s a shame here, in discussing pain, especially chronic pain and mysterious not-quite-chronic, in-and-out, there-not-there pain. No one wants to be a complainer, after all. Does my mother, just now in her sixties, on her feet every day serving people at the grocery store deli, complain? If she doesn’t, what right have I? Am I going to whine to her about the injuries I’ve received, when I make at least marginally more money than her (and no children to support!) while writing email? While typing?

Though I refused to acknowledge it for a long time, I do know the pain that often starts when I sit down to work. My precarious freelancing and contract-worker self, always in search of coffee shop seating, will at last find a place to open my laptop, only to think about getting up and leaving again a mere ten minutes later. My wrist will be agitated. I will pop my left shoulder back and forth, roll my neck around, try to find some posture where the muscles tense just a little less. If only I can get into a space of concentration for long enough, my mind will be occupied so thoroughly that it won’t notice the hurt. Up to a point. That point—in which my upper body’s throbbing muscles and hot joints scream loudly enough to tear down all my mental walls—will come in about an hour. I lean into my screen, intent on getting through as much as I can in that time.

“Freedom means facing up to what’s killing you, healing the damage, and becoming in-different to the lure of sacrificial promises of monied or exclusive happiness and the familiarity of your own pain.” This is sociologist Avery Gordon summarizing Toni Cade Bambara, through a reading of Bambara’s short fiction as well as The Salt Eaters, all works in which the characters must sort through their pain and its link to freedom: both the unasked-for pain dished out by the world, and the pain one can make for oneself, especially in the quest for freedom, especially if one has any confusions involving freedom as an object to be achieved or handed out. For freedom isn’t a place where we arrive, as Gordon reads Bambara, but a process or practice: “Freedom is the process by which you develop a practice for being unavailable for servitude.”*

* Avery F. Gordon, “Something more powerful than skepticism,” in Keeping good time: Reflections on knowledge, power, and people, pp. 187-205. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2004.

“The familiarity of your own pain”—it tripped me up, the first time I read it. My pain is familiar, but in a shadow companion kind of way. I keep it at a distance. More shadow as apparition than as friend— something seen via sideways glances, never head on. Facing up to it might tear open too much, expose all the ways my pain and precarity have been linked, how the tools that I have used in hope of escaping both keep turning out to be double-edged. How they keep me available for servitude.

There was one brief period where I felt granted permission to talk about pain. This was right after I had, verifiably, nearly died. When a car runs a red light, breaking both your bicycle and your face, sending you to the ER and then into cardiac arrest, people expect that you will hurt. If you try to play tough, laugh it off, they remind you to take your time. “It’s okay to rest,” I heard more than once. “Life is not supposed to be ‘normal’ right now.” But for how long? Six months? One year? Two? What happens when all visible traces of injury disappear? What do they expect then?

For most injuries, there’s a day that arrives when your pain remains, yet others can no longer interpret it without assistance. When I returned to riding the subway after the crash, my stitches, bruises and unsteady gait were enough to earn me the offer of a seat from strangers. As time wore on, such encounters became more fraught. For I didn’t know: was I strong enough to hold myself up today? Even if I knew I wasn’t, how as a young thirty-something did you make an ask of others to let you sit down? I continued wearing a wrist brace even after it wasn’t strictly necessary, the only visual trapping I had to offer when the stitches healed, as most of the major damage remained internal, invisible.

And then I was better, the subway strap a non-issue, until years later I wasn’t again, when the side struck by the car that fled into the night would stiffen or burn or both, my muscles responding by becoming tense, fortified structures, protecting some part of me I couldn’t even quite identify. My left shoulder felt as unpliable as a stone wall, all bricks and mortar. I demonstrated this to my physical therapist by pounding upon it repeatedly with my right fist, an act that did not hurt me in the moment but caused her to cry out, “Stop! Stop!” and when I relented she chided me, “Gentle with your body.”

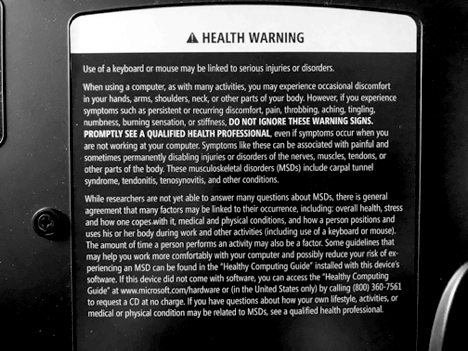

What we began untangling in a multi-year process is the way in which damage from the hit-and-run forged literal knots with the repetitious injuries from work in front of a screen. All that tensing and burning I had been ignoring—presuming it something left over from before, not something I was actively doing to myself daily— was pain my PT refused to overlook. She asked if my workplace had resources to help with ergonomics, which sent me laughing: “The places I work, you for sure bring your own computer, if not your own chair!” But we did some trouble-shooting, and I promised to work out of coffee shops less, to elevate my screen at least some of the time, to acquire a separate keyboard. Absent from every laptop I’ve ever used, somehow my “good” keyboard arrived with a warning label:

Photo courtesy of the author

What a prompt to make one consider: How do we face up to what’s killing us when it seems to be the very tools that provide us with a living?

How many of us have thought that we were practicing freedom, when the very tools of our practice were engendering the opposite?

I’m not even using the “good” keyboard right now, anyhow. It made me hurt even more than the laptop.

I had thought myself “in-different to the lure of sacrificial promises of monied or exclusive happiness,” never pursuing the well-paid or high- status jobs my college peers went in search of. Yet I had been duped not once, but twice, by such “sacrificial promises,” as they were reliably offered up by the education-student debt machine. Though I recognized the trick at last, after which my becoming “in-different” meant dropping out, taking the MA but forgoing the PhD. I wouldn’t take the lure, and I would be fine with the lack of money, I said to myself, which certainly wasn’t a given on the academic track anyhow, despite all the institutional reassurances of professorial prosperity. Debt, I was learning, was one of those double-edged tools that came without a warning label, promising a way out of precarity or pain only to deliver new forms of each.

Still, I thought I could be exceptional, and escape the snare that debt set for so many others. I knew that debt had been a pathway to servitude of the variety I grew up witnessing my mother experience. I reasoned that what had seemed to keep her trapped was not low-wages, per se, but the chasing of the dream of living beyond them. We had existed in the murky not-poor poor way of many U.S. whites, the occasional yet routine need for food stamps and free lunch tickets made all the more miserable by lines of credit resulting in consumer goods always around but always breaking or in need of repair, bonding one to bills just out of reach of finally paying off, leading to bankruptcy and garnished wages and the whole bad mess of it. Broken piles of plastic toys and credit card bills my mother hid away were the relics of these faulty attempts at a misguided sense of abundance.

There would be no more debt for me, I assured myself, even as I carried a growing sense of foreboding that rent would be a forever form of debt I could not escape. I would make it be okay, and mostly did, adopting an attitude of permanent, creative frugality aided by tendencies toward communal living and anti-consumer environmentalism. Both need and habit, then, cemented my conviction to avoid the one form of debt that above all others I associated with that misguided pursuit of middle-class false abundance, the biggest plastic toy of them all: cars. No car loans for me, no monthly insurance payments, no having to buy gas just to get somewhere. Automobiles were clearly the most clever of debt traps, as once you had one, you locked yourself into life patterns, housing and job locations, that required you to immediately replace the vehicle should it ever break. That they would always break, to me, was just a matter of fact. One of my earliest memories is my mother buying a used car only to have it break down on her way home from the sales lot.

This is how the attempt to avoid servitude by debt led me to bicycling. A used bike required little money up front and no regular day-to-day cost, unlike bus fare, and I could make most repairs myself. Which means that one way of telling my story could be that my attempt to escape precarity was nothing but yet another false step, my twenty-something able-bodied hubris oblivious to the real risk of collision and injury; that it was the cause of my eventual near death and an encounter with the most insidious debt trap of them all—an American hospital, where I spent a week on a heart monitor, raccoon circles under my eyes and a bureaucrat pushing billing papers in front of my concussed vision.

My life, it would seem, has become an uneven experiment in resisting the dominant social and physical technologies of the 20th century, with mixed results. Cars, computers, and credit: they come loaded with a bevy of advertised benefits. Cars and computers, especially, are sold with a promise of simultaneous escape and access, of autonomy and transcendence. Yet in reality they cut short any true fulfillment of these through their outright denial of physical reality and our actual, physical bodies. Through their promise of a fantasy mobility, they physically immobilize us: one sits in front of a screen, then moves slightly to sit in a car in traffic, all routes to unencumbered motion cut off by the need to remain in communication with the object ostensibly “taking you places.” They are precisely “a lure of exclusive happiness” that trap us into distorted and injured forms of our own selves, delivering not escape and transcendence but calcification and torpor, an inability to use one’s own self, as wrists stiffen, glutes weaken, hips lock, and our practice of movement atrophies.

Credit, or debt, similarly promises a social mobility, a transcendence of one’s current financial status, the opportunity to move beyond current limitations and come closer to a glimmering dream of the future. Only in its current configurations it likewise restricts mobility, if not outrightly forcing movement in the opposite direction from what its holder intended, as they find themselves working more hours to pay off interest and additional payments, and that moment of “getting ahead” or simply respite from the game of “getting by” never arrives.

The rapid transcendence of these technologies makes them feel necessary, as though there is not a free choice to be made about their use. The lack of choice, while manufactured, is not entirely an illusion; as presently structured, they both operate in the manner that Ivan Illich, in his Tools for Conviviality, calls “radical monopolies.” In a radical monopoly, the infrastructure set up for a given tool to be useful increasingly requires ever more use of that tool, and stymies those who would opt out. According to Illich: “Radical monopoly exists when a major tool rules out natural competence. Radical monopoly imposes compulsory consumption and thereby restricts personal autonomy.” More simply: cars make it difficult or impossible to walk. Computers cut off other routes of finding and sharing information. A credit-based financial system denies work or access to good to someone lacking a past history of debt—i.e., a credit score.

This, despite the cost we know they bring: oil spills, gas explosions, and 1.35 million killed on roadways globally each year. Wars over coltan, mass suicide at Apple factories, mercury and lead leaching into drinking water. The harm spills over not just on the production side, but for users, our individual bodies. And then it scales back up again: debt destroys not merely individual livelihoods, but captures the foreseeable future of untold generations in nations who have taken on IMF and other loans.

These radical monopolies, with all their varied harms, have predictable sources. Both the car and the computer make labor accessible to serve capital as needed; one allowing labor to travel to a factory or office, another allowing it to be captured wherever it might be found—at home during a pandemic, say. Credit has become requisite for accessing basic goods—housing is the obvious example—reinforcing the need for additional labor to access the resources to pay off such debts. Radical monopolies are precisely those tools that make us available to servitude. Available not only for an employer, but for the expansion of the monopoly of the tool itself.

So here I am again, asking: how do we face up to what’s killing us when it seems to be the very tools that provide us with a living? Resistance to radical technological monopolies isn’t simple (surprise!) and while Illich’s writing does a fair job of elaborating the need to challenge them, I don’t think he does much to guide us about where we might go next. What, for instance, might Illich think I should do with my keyboard?

I tried to face the truth of my keyboard’s apparently murderous intent—or if not intent, its impact—more squarely, in late 2019. I made a New Year’s resolution to move more of my work as an organizer off of email and into real life, in-person conversations. In early 2020 I took a sabbatical of sorts, to think about what it might mean to earn a living without a computer, and worked instead on a small farm.

The job on the farm was temporary, but offered the chance to begin thinking about what it might look to resist the radical monopoly of computing technology. We have ready tools and capacities to use in resistance to the car monopoly, from feet to bikes to wheelchairs and more, but what does it look like to practice, or exercise, in resistance to the radically dominant presence of computers in our lives? We can’t all be farmers... or can we? Even those in agriculture are finding themselves integrating digital technology in fascinating ways, from sophisticated monitoring systems to the farmers of Instagram. Even they will face a choice: do I allow such tools to trap me into permanent use, to make my own movement upon the land unnecessary, or will I keep up and exercise my right to exist not just on the land but with it?

I was still on the farm at the moment news of the coronavirus broke out. As the weeks progressed, I saw my intention to break from the dominant mode of action, from the radical monopoly of a given tool—in this case, heavy use of computers and the internet—once again transform into isolation, a cause for self-doubt, and a reinforcement of my own potential precarity, as opportunities for work that once might have been at last partially physical or offline were quickly rendered digital.

While my work on the farm ended, I never returned to my position as an organizer, for a multitude of reasons, but in part because I knew: writing even more emails and attending daily meetings over Zoom, for me, would not be a way to survive the pandemic. These things had been killing me long before COVID-19, and they were ready to get competitive with whatever viruses wanted to take their place as the delivery mechanism for my body’s final immobility.

Let’s not pretend that I have in any way separated from computer usage. At best, the year has given me time to attempt new modes of mediating that usage, be it dictation tools or tablets that convert handwriting into typewritten text. Financially, I made it through the pandemic solely on the luck of being in relationship with someone who could afford to pay my living expenses as well as their own, and opted to do so.

However, in a year that saw many people massively increase their time online, I was able to cut out large swaths of time for myself away from screens. Enough time to tilt my head a little further (with a little less pain) and squint at them, to see if the pain was worth whatever promised goods they managed to deliver. Mostly, from that vantage point, our laptops and phones often look like just another failed attempt at a false abundance, a trick to keep us in place and away from the fullness of the world. Broken plastic toys replaced by broken electronics and digital detritus.

The results of my resistance to the traps of such false abundance has been uneven, yes. But reflecting on all my efforts here allows me to see that they are, still, resistance: a practice of being “unavailable for servitude.” Which suggests that there is room, yet, for challenging the radical monopolies that seem to limit our choices and the very motions our bodies are capable of making. That room is easiest to claim when we cease trying to pretend as though the current system is painless—that my desk “job” doesn’t hurt me, that school loans didn’t hinder me, that I don’t walk with the threat of death each day just by walking down the street next to speeding vehicles. I can let my pain come into full view, rather than forcing it into the shadows. I can face up to it, and see that while its sources promise me a living, that’s not what I’m getting. I can tilt my head again and see if there’s room to create space, even an inch, the slightest bit of distance to make myself, if not fully “unavailable,” at least less so.

I can close the laptop lid and be done, if not for always, at least for now.

You can find more of Meg's writing at unsettling.substack.com.