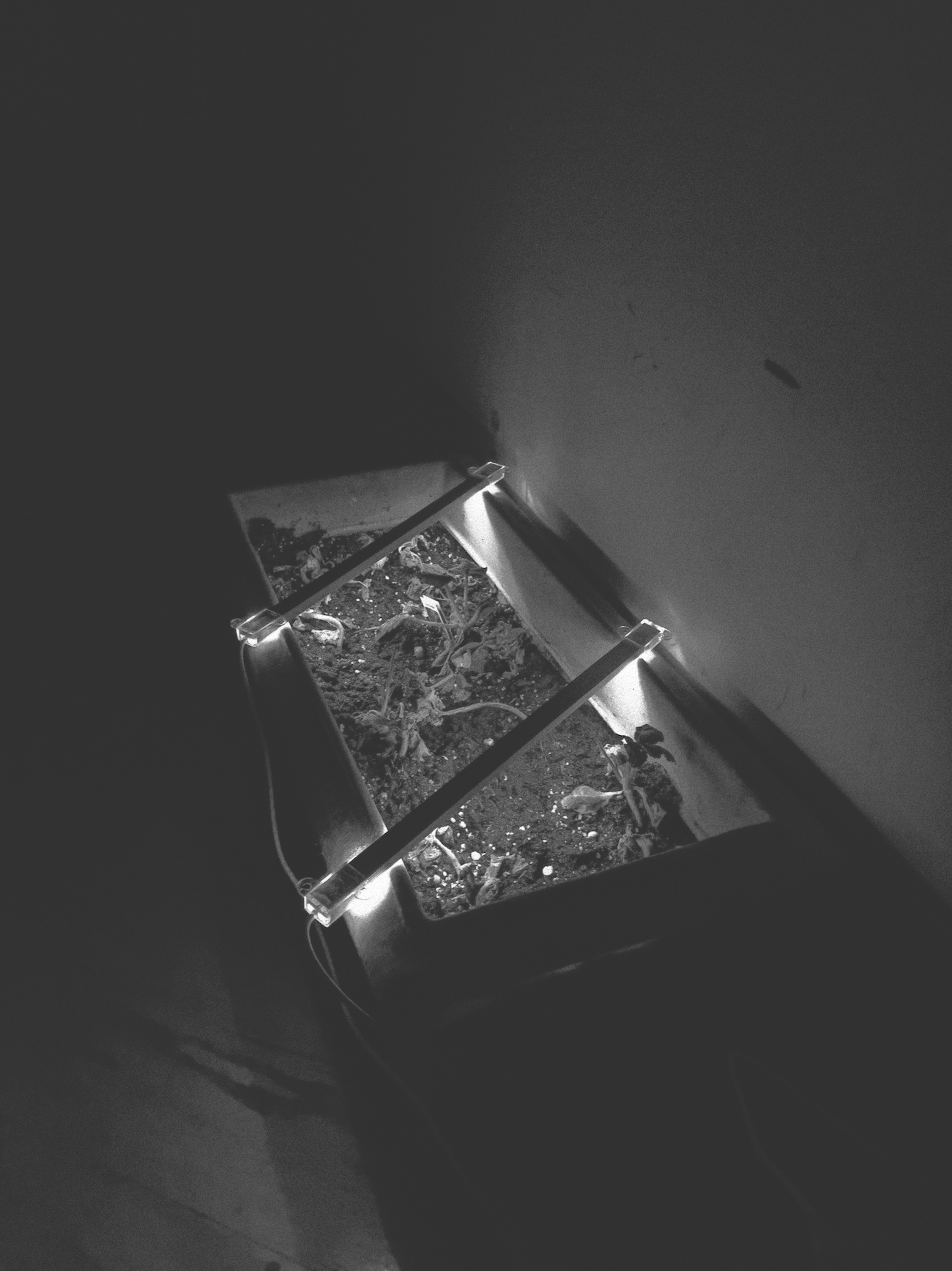

As unlikely as it may seem, small utopias are all around us. From indoor gardens illuminated by ghostly grow lights, to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle formed during protests against police violence and the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, to the strengthening and spreading of mutual aid networks providing food and bail money in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are, perhaps, in a golden age of building infrastructures for futures yet to come.*

As a scholar who studies the production of scientific knowledge and new technologies, I wonder what kinds of know-how will be crafted with and through these projects, artifacts, and networks. Will the proliferation of small utopias provide new models for social behavior that center cooperation and the pursuit of justice for all, instead of competition, self-interestedness, and resource scarcity? Will these renewed experiments in protest culture and mutual aid produce openings for knowing society differently, beyond limited laboratories of hope within activist communities? I am hopeful that the answer may be “yes” for many reasons, personal, political, and scholarly, in the current pandemic moment.